Since the first Academy Awards in 1929, no woman had ever won an award for best director until 2010. Kathryn Bigelow with The Hurt Locker (2009) was the first and only woman to win the award, and only the fourth woman ever nominated, out of more than four hundred nominations. For many years, women’s role in the film industry has been limited. In Canada, in the 1960s, some women worked at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), but mainly they were working in supporting positions, such as secretaries. They rarely worked as producers or editors. However, influenced by the second wave of feminism in 1960s and 70s, women at NFB challenged the male-dominated film world by persuading the NFB to create the first and only government-funded female filmmaking unit, “Studio D.“ Studio D reflected feminist ideas of the 1970s in its most important films: Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography (1981) and If You Love This Planet (1982).

Since the first Academy Awards in 1929, no woman had ever won an award for best director until 2010. Kathryn Bigelow with The Hurt Locker (2009) was the first and only woman to win the award, and only the fourth woman ever nominated, out of more than four hundred nominations. For many years, women’s role in the film industry has been limited. In Canada, in the 1960s, some women worked at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), but mainly they were working in supporting positions, such as secretaries. They rarely worked as producers or editors. However, influenced by the second wave of feminism in 1960s and 70s, women at NFB challenged the male-dominated film world by persuading the NFB to create the first and only government-funded female filmmaking unit, “Studio D.“ Studio D reflected feminist ideas of the 1970s in its most important films: Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography (1981) and If You Love This Planet (1982).

The feminist movement in the 1960s and 1970s, which was sparked by Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique (1963), inspired feminists to make organizations for women and translate their ideas into media. In terms of documentary filmmaking, women entered from two directions: one in which feminists believed that film was an effective “tool for raising consciousness and for implementing social changeâ€, the and one in which women already working in the film industry “chose to explore their own feminist consciousness on film.â€

Studio D, the new studio “by and for†women, was established in August 1974 by three women filmmakers; Kathleen Shannon, Margret Pettigrew and Yuki Yoshida. The studio had two objectives: to project women’s perspectives in its documentaries†and “create opportunities for Canadian women in a field traditionally dominated by men.

The challenge of creating a women’s studio had occurred when Shannon recognized that the NFB did not express the opinion of women who made up fifty three percent of population, that means half of Canadian population, and failed in its mandate to “interpret Canada to Canadians and the rest of the world.

In addition, Shannon had felt that women were still unequal even at the NFB. Although the NFB treated women’s issues in its films, technical areas had not been opened to women because of a gender bias that “women don’t understand electricity†and “women don’t have physical strength. “ She thought the male-centered film industry should be changed, and that a place was needed where women could express their voices and have access to responsible positions. Indeed, Studio D did not receive enough funding and additional staff, so her plan to make an “all-women†studio was not achieved until 1985. However, she played a great role in bringing filmmakers together and giving them opportunities to create and share their feminist voices through films. Until its closing in 1996, Studio D produced more than one hundred fifty films, including one of its most important films, Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography (1981), and won more than one hundred international awards including three Academy Awards for I’ll Find a Way (1977), If You Love This Planet (1982) and Flamenco at 5: 15 (1983).

Not a Love Story: A Film About Pornography (1981) is one of the most popular and controversial documentary films made at Studio D. The film was directed by Bonnie Sherr Klein and produced by Dorothy Todd Hénaut and it aimed to raise women’s consciousness about pornography. In the film, on-screen director Klein and stripper Linda Lee Tracy explore the various areas of the pornography industry, such as “porn shops, sex booths, live sex shows, “hard-core†magazines, and photographs of women in bondage†and present many different insights on pornography through interviews. They hear the opinions of workers in porn industry, such as Suze Randall, an erotic photographer for Penthouse, feminist writer Kate Millet, Susan Griffin and reformed porn actor Marc Stevens, talk about the degradation of women caused by the industry. In addition, Klein and Tracy actually visit a red-light district in New York and their “graphic, sleazy events†are shown by “intercutting hard-core pornographic film clips and photographs.“ Klein uses voice-over narration and presents the fact that the combined circulation of sex magazines Playboy and Penthouse is greater than that of TIME and Newsweek put together, that the pornography industry’s annual income has grown from five million to five billion dollars in a dozen years and that “it is larger than the conventional film and music recording industries combined.†Moreover, she argues that there are more than twenty thousand pornography outlets across North America which is four times as many as MacDonald’s restaurants.

A notable point of the film is the change in Tracy’s view on pornography. In the beginning of the film, it seems she already has some questions about pornography, but Tracy explains, with the footage of her comedic performance of “Little Red Riding-Hood,†her act as stripper is “a parody†of eroticism and she does not consider that it is degrading women because she “is in control of her act and aware of her sexuality.†However, as Tracey learns more about pornography through the interviews and experiences, her views on pornography gradually change. Finally, at the end of the film, when she is asked by Randall to pose for a pornography magazine, she finally realizes women are humiliated “to satisfy men’s desire for dominanceâ€Â and begins to question her own work and its contribution to the exploitation of women. Feminist critic, B. Ruby Rich, read the film as a “religious parable†in The Village Voice. Others questioned Tracy’s honesty in reconsidering her attitude to the pornography industry. In an interview published in the Haymarket newspaper, Klein commented:

I think that such a criticism is extremely condescending to Linda. She actually continued to work as a stripper for six months after the film was completed to be sure of her decision to quit. She finally realized that she had been lying to herself. Linda started to hate her work and to lose her sense of humor about it. She actually became physically ill from it.

Due to the sensitive subject, Not a Love Story (1981) received much criticism. Even though Klein intended to show that “pornography is not about sex or eroticism, …but a power relations between men and women†through the film, it was banned from theaters by the Saskatchewan and Ontario Censorship Board because of its sexual content. However, when the film screened at limited educational venues, more than forty thousand audience members were attracted within a year in Ontario alone. Furthermore, the film succeeded in provoking international debate on the issues of pornography and censorship and brought a discussion of pornography to mainstream Canadian politics. Therefore, the film had an impact on society beyond the women’s movement .

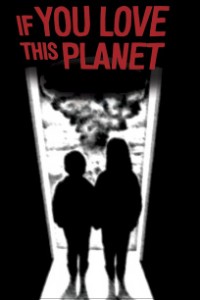

If You Love This Planet by Terre Nash, National Film Board of Canada

If You Love This Planet (1982), directed by Terre Nash, is another film that attracted much attention and it is one of Studio D’s three Academy Award-winning films. In the film, the president of Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR) in the United States, Dr. Helen Caldicott gives a lecture to university students about nuclear war, and calls for the disarmament of the United States. The film mainly consists of talking heads and war-related footage, and there is no voice-over narrations used to insert other opinions on the subject. Early in the film, the footage of JAP ZERO (1943), the United States Department of War information film, and a wartime newsreel featuring then President Truman who ordered atomic bombing to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, are intercut. While showing archival footage of the bombing, nuclear explosions and images of its survivors, Dr. Caldicott explains about the medical consequences of nuclear weapons, and what will happen to other countries if nuclear powers, such as the United States and Russia use the weapons. The film sometimes shows the audience faces filled with fear and grief, and even tears in close-up. These help to emphasize Dr. Caldicott’s strong emotional message that nuclear weapons â€must be eradicated from the worldâ€Â to viewers. As well as Not a Love Story (1981), If You Love This Planet (1982) was banned in the United States because it was regarded by Ronald Reagan’s Republican administration as political propaganda, a film that would “influence a recipient or a section of the public within the United States with reference to the foreign country or a foreign political party or with reference to the foreign policies of the United States.†However, the film won seven awards, including the Oscar for short documentary, and proved “the ability of feminist documentary to undermine traditional patriarchal values on military and state matters. “Likewise, Dr. Caldicott also proved the importance of standing up and taking actions by oneself, and that feminists have power to make their voices heard and achieve social change.

Along with criticism of its films, Studio D received criticism for its structure. In creating a new women’s studio, Shannon had a radical vision to change the whole film industry by reflecting a particular feminist view point into documentary films focusing on women’s experiences. An important point in having “separate women’s institutions†was to ensure an environment where women alone could think and express their unspoken and unexplored views, without being put under the control of men. Some pointed out being a separate institution might have created a “women’s ghetto,â€Â a collective of middle-class white, liberal feminist, that have bias against class and race. In contrast, based on the notion of Virginia Woolf that “if women had a room of their own they would be able to develop the habit of freedom†and speak (create) in their own voices, “ others, including a cultural historian Chris Scherbarth, described Studio D as a “women’s room, “…“a brave (and radical) pioneer into the world of film by and for women.†Shannon also reacted negatively to the notion of “women’s ghettoâ€: “Ghettos are where others put you, in their minds. Studio D is where    we wanted to be, it wasn’t a ghetto but a refuge. Besides, no one ever alls all male institutions a ghetto.â€

In truth, Shannon herself hoped to have a diverse group of female filmmakers, but Studio D had long suffered from budget problems, which prevented her plan. After Studio D started with a small budget of $100,000 in 1974 , its budget fortunately was increased by six times to $600,000 by 1975Â to 1977, and continued to increase to $853,000 by 1977 to 1978. On the surface, the budget growth seemed to allow Studio D to hire and train additional staff, but in fact, having its headquarters in Montreal, there were ten national studios, including Studio D, in English branch of the NFB. Therefore, Studio D had to cover staff, services and overhead with the budget shared by the ten studios, and only once did Studio D receive ten percent, which was the maximum budget it ever received in its lifetime. Studio D did not hire new staff until the early 1980s.

In 1986, after Shannon was awarded the Order of Canada “for her extensive contribution to women’s role in filmmaking, “she stepped down as an executive producer of Studio D due to the stress caused by several controversies, while she continued to work for the studio until 1992. By 1987, Rina Fraticelli was chosen as the next executive producer because of her experiences as a feminist activist, publisher and theater art administrator, and she tried to reorganize Studio D to represent more diverse views by increasing hires of “filmmakers from outside the majority white middle-class culture of Studio D.†In 1991, New Initiatives in Film (NIF), a program aimed at addressing “the under-representation of Women of Colour and Native Women in Canadian film†was launched. Similar to NFB’s previous Challenge of Change program, NIF provided these women with an opportunity to receive training and express their own voices, and Studio D worked with the “external independent women’s production groups†until 1996 . Nevertheless, in spite of their efforts to solve the concerns about diversity, Studio D unfortunately was shut down in 1996, amid a hostile political climate and “the money crunch,†government budget cuts in the1990s. During the period, federal government decided to reduce public spending and government regulation across Canada. In January 1996, the government published a report of the Mandate Review Committee, which sought about twenty million dollars in cuts for three years. As a result, the NFB needed to reorganize its branches, and the closure of Studio D was decided.

With the resurgence of feminism in the 1960s to 1970s, women gained strength and sought the empowerment of women. A product of its time, Studio D was a separate women’s institution used to express feminist ideas free from domination by men and sought to achieve gender equality. The films created by Studio D often focused on women’s lives or experiences and, by reflecting how women were defined socially and culturally, they intended to raise people’s consciousness and motivate actions on women’s issues. Not a Love Story (1981) and If You Love This Planet (1982) are two of its most important films, and each film explored in depth two important concerns of women- the pornography industry, and the danger of nuclear weapons-and provoked international debates on the subjects. Despite their valuable contribution to women’s film and efforts to be diverse, Studio D was sometimes labeled a “women’s ghetto†which expressed white, middle class feminist ideas, and finally closed in 1996. However, t it received many awards -including the Academy Award for three films,- and, as the NFB’ s most successful film unit, it was described as a“ national treasure.â€Â Today, inequality between men and women in the film industry still exists, but Studio D showed that film is a good medium to promote social change and the efforts of the women involved emphasizes the importance of standing up and taking action.

Further Reading

Vanstone, Gail. D is for Daring: The Women behind the Films of Studio D. Toronto: Sumach Press, 2007.